New River Adventurers

by Olivia Ahmad, Quentin Blake Centre team

This Heritage Treasures Day we’re publishing New River Adventurers, a report by historian and writer Dr Angelina Osborne, illustrated by Cat O’Neil. Angelina’s research has found that money made from overseas trade and colonisation was invested in the New River project.

Our Artistic Director Olivia Ahmad spoke to Angelina and Cat about researching and interpreting colonial histories.

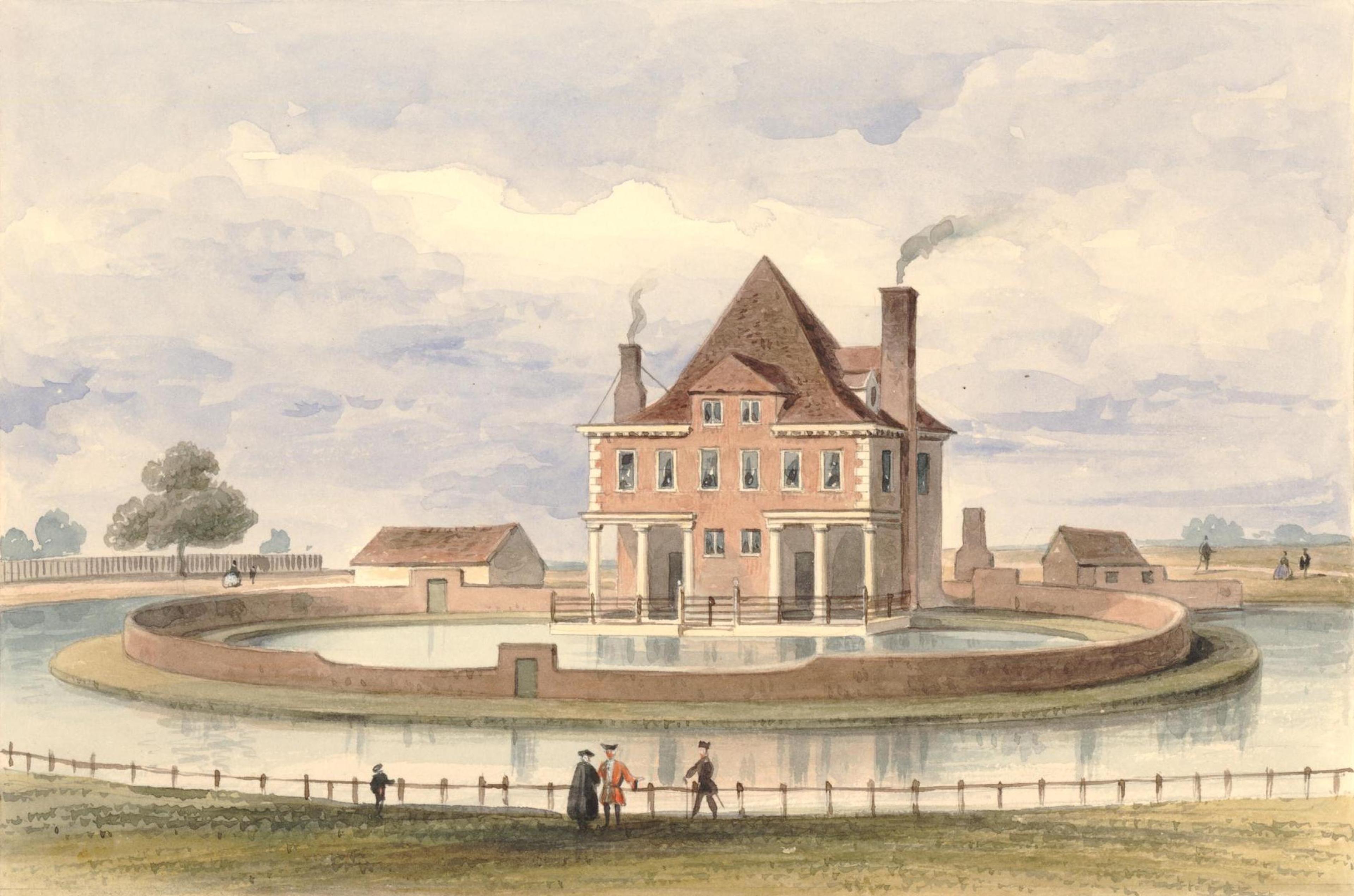

Next year Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration will be relocating to New River Head, a former waterworks in Clerkenwell, London. There’s a lot of work to do before we move in: the buildings are in serious need of repair, leaking roofs need to be fixed and smashed windows need glazing. We also have work to do to understand the site’s story.

New River Head was established in 1619 and was the headquarters of the New River Company. In a way its story is simple: London’s growing population needed clean water and a network made up of an aqueduct (the New River), ponds and pipes was made to supply it. But there is more to know.

In the late 1500s and early 1600s, wealthy people in the City of London started pooling their money to invest in the often risky and exploitative enterprises of overseas trade and colonisation, as well as piracy (or ‘privateering’), which involved the trade of stolen goods and enslaved people. Some made huge sums of money that was spent on projects at home. We knew that the New River project was a costly one and that a group of 29 people known as ‘the Adventurers’ had put up the money. But we didn’t know if that money had come from theft, enslavement or colonisation, and so we commissioned Dr Angelina Osborne to find out.

Colonisation is the process of one people settling among and establishing control over the Indigenous peoples, as well as the land. Britain colonised many places from the 17th century onwards. This had many consequences, including the imposition of violently enforced laws, forced labour, the extraction of resources and suppression of indigenous cultures. These continue to influence our society today. “We all operate through colonised perspectives” Angelina says. “European culture, philosophies, political thought and academic disciplines are seen to have value over the perspectives of oppressed groups. Some define ‘decolonisation’ as challenging and interrogating these Eurocentric perspectives and giving more consideration to the perspectives of oppressed or marginalised groups - these groups call for their perspectives to be included, in opposition to these received ideas.”

The New River Company was founded in the early 17th century, the period before most recent research projects tracing colonial wealth. “I was interested in learning about early examples of profits from colonial ventures being used to create British infrastructure” Angelina says. “We know that profit from enslavement in the 18th century helped to fund railways, parks monuments and museums. However, for me, it was fascinating to investigate where this all began.”

The activities of a company founded more than 400 years ago can’t be found with a simple Google search. Angelina trawled through original material and digitised archives to find out about the Adventurers’ lives and business interests. “It’s a lot like detective work” she says, “you ask questions and see which ones you can answer.”

Sometimes there are gaps in the record. “The original minutes of the New River Adventurers' meetings were lost in a fire during the war, which was a slight setback” Angelina explains, but “knowing that many of them were members of the powerful livery companies was a great starting point.”

Livery companies were established as trade associations and the Adventurers had affiliations with several, including the Goldsmiths, Grocers and Drapers. “I thought these companies were likely to have invested in colonial ventures and I was right about that” Angelina says. “I also figured that since many of the Adventurers were part of the merchant classes they were probably members of parliament, because what better way to protect your interests than to be in parliament, or government or the law?” To find these connections, Angelina looked through the Calendar of State Papers, extensive documents that “cover much of the legal and political information of the late 16th and early 17th centuries” she explains.

It’s a long and laborious process. “A lot of the time research is like panning for gold” Angelina says, “you spend hours sifting through dirt to find little nuggets, but it's worth it in the end.”

Angelina’s work has found that money flowed from global enterprises into the New River Company, with at least 19 of the Adventurers profiting from privateering (state-sanctioned piracy) and investment in the Virginia, Guiana, East India and Somers Island (Bermuda) companies. She explains, “my research did not find that the New River Company’s founders were involved in enslavement (as systematic involvement did not begin until the 1660s), but it shows that they invested in activities that laid the foundations for colonial investments and the creation of colonies in North America and elsewhere.”

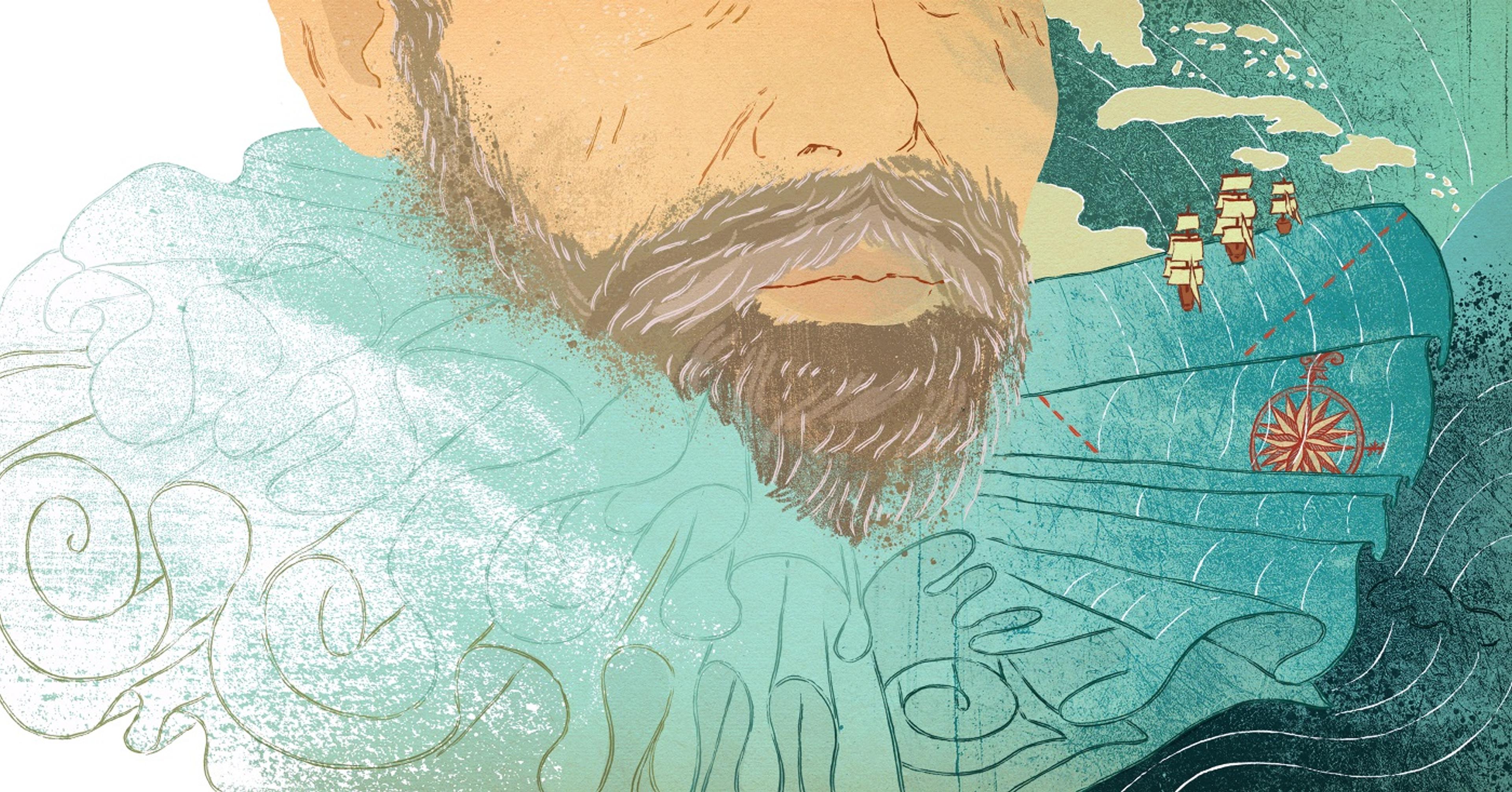

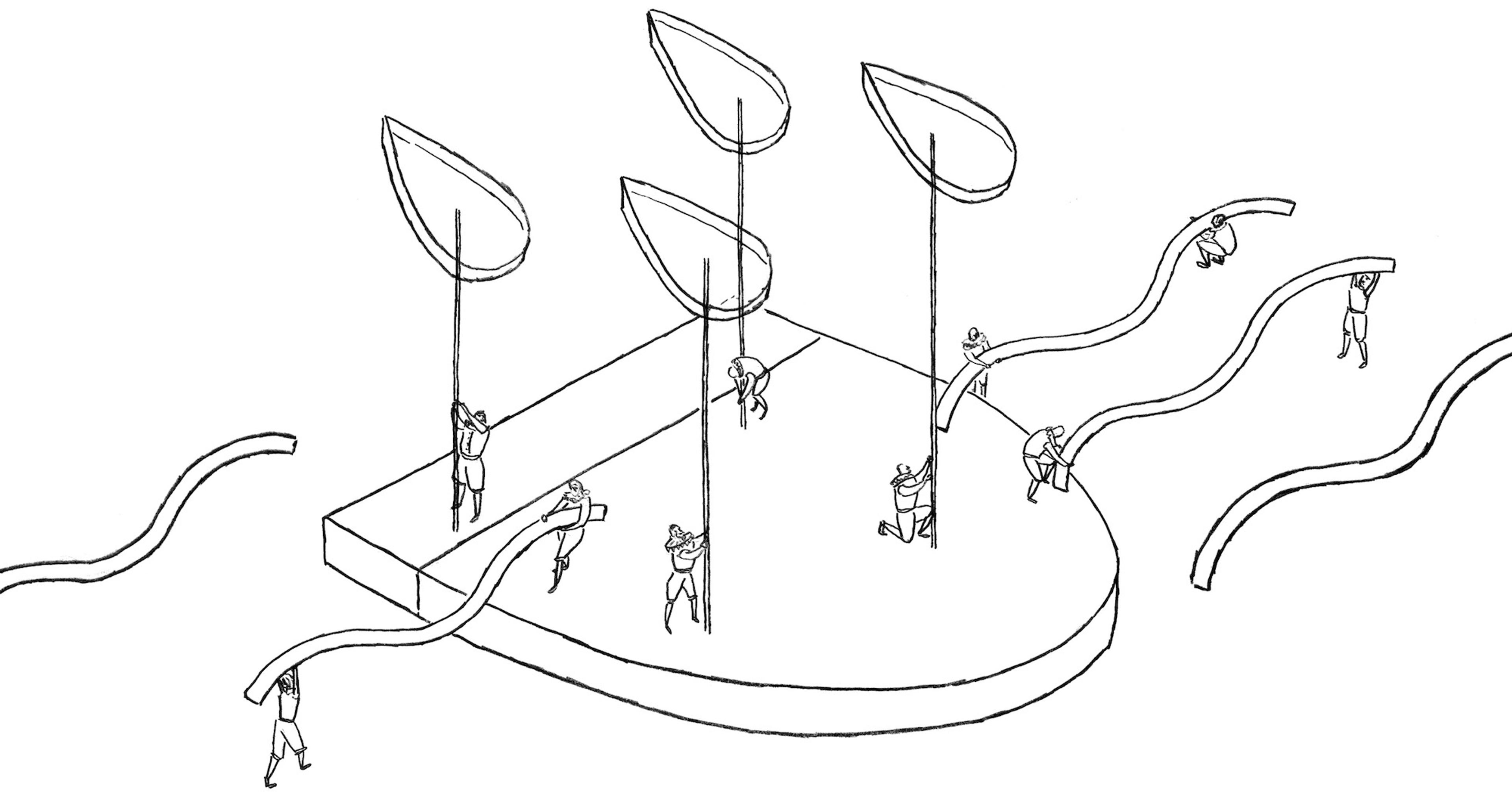

We commissioned Cat O’Neil to create a series of interpretive images to accompany Angelina’s report. She brought both experience of visualising colonial histories and a personal perspective. “I care a lot about doing justice to the emotional gravity of these projects, so I spent a good amount of time with the source material and reading around the subject. But an important aspect of this work is that I’m of mixed heritage myself, being Hong Kong Chinese and British. I spend a lot of time reflecting on race, nationality and what ‘home’ and being British means, so the subject of colonialism is ever present.”

Working to decolonise history is challenging. It involves recognising exploitative practices that have had negative effects on people while taking care to avoid further exploitation and highlighting only the perspectives of those who benefitted. “Although the report is about the founders of New River Company, Angelina and I wanted to take the emphasis away from individual founders and their stories” Cat explains. “We were more interested in visualising the actual legacy and implications of their actions.”

To do this, Cat used a series of central visual metaphors, creating many more rough composition ideas than usual for a project. “I used motifs such as the clothing of the time that indicated wealth and status” she says. “I looked at a lot of ruffs! There was something visually poetic about having the ripples of the fabric flowing into waves of the sea and alluding to the future of colonialism and wealth extraction, with the West Indies seen in the distance.”

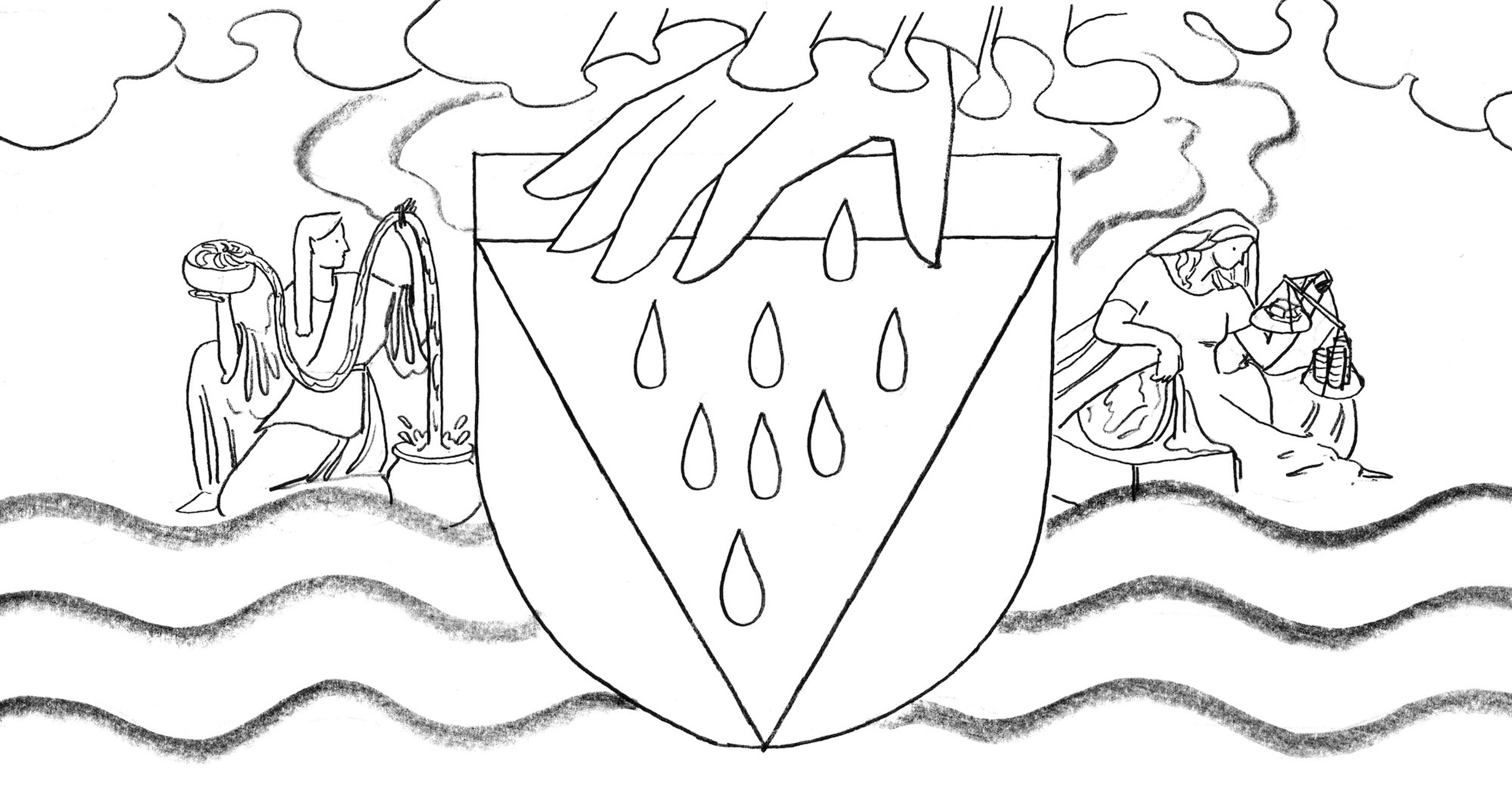

Cat also used the design of the New River Company’s seal, inspired by a 1930s version still at New River Head. “I was very taken with this beautiful Art Deco motif, but I felt a tension about it that reminded me of the Palais de la Porte Dorée in Paris. It was previously the Paris Colonial Exposition and is filled with these incredible Art Deco murals that are essentially propaganda for colonialism. It’s deeply uncomfortable. The artwork is so beautiful, but it’s all a lie: in some places it’s covering up something awful and in others explicitly describing something awful but presenting it as positive. This building is now home to the Museum of Immigration, which is an extremely interesting choice of venue. I thought a lot about this building and the museum working on this project.”

We commissioned this study to bring depth to New River Head’s story, and a new understanding of how it fits into a bigger national and international picture. “The work I have done here is part of a current trend of revealing all aspects of the histories that discuss Britain’s colonial projects” Angelina says. “I think raising awareness about British history’s complexities is vital and this report is a great beginning for understanding New River Head.”

We have made an application for funds to continue research into the New River Company’s shareholders from the mid-17th to the late 19th centuries. We will try to find out who the shareholders were, and what they did with the money they made from the New River Company. This research will be part of our wider work collaborating with communities, illustrators and researchers to explore and share the story of New River Head and its impact locally, nationally and internationally.

If you have comments, questions or suggestions on our research and plans, email info@qbcentre.org.uk.

Illustrations by Cat O’Neil generously funded by the Barbara and Philip Denny Trust.