A Q&A with illustrator Sharpay Chenyuè Yuán

by Sharpay Chenyuè Yuán, Quentin Blake Centre resident illustrator

Illustrator Sharpay Chenyuè Yuán is our first Engine House Graduate Illustrator-in-Residence. Last year, Sharpay spent time at New River Head, the derelict former waterworks that will become the Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration. Ahead of showing her work this September, she tells us more about using drawing to investigate the past.

How can illustration tell us about history?

Illustration can be a bridge between the past and the present. I am really attracted to stories about the past, especially when they have continuity with what I see at the moment.

My illustration has a kind of softness that means I can combine things from different times and make unexpected connections between them. I bring together people’s memories, things I observe, archival sources and a little bit of imagination. This could be seen as less precise than written ‘facts’, but to me the ambiguity of my images corresponds to the complexity of history itself.

Have there been any particular places that have inspired you?

Before the pandemic, I spent a lot of time at Shepherd’s Bush Market in West London. Besides buying my regular groceries, talking to merchants who were working there became my routine. I began collecting stories: one slender grocery store owner was once an arms trader in his home country, the spice store was once a cover for secret trade and under the shops lay a network of tunnels.

These stories inspired me to find out more about the market, and I found stories from the distant past with connections to those the traders had told me. I created a series of illustrations about these connections. One of my favourite links scattered fish heads from a 1920s archival account of the market with complaints about the smell of fish in the market today and my own observations of the work of the fishmongers.

Have you worked with archives on any other projects?

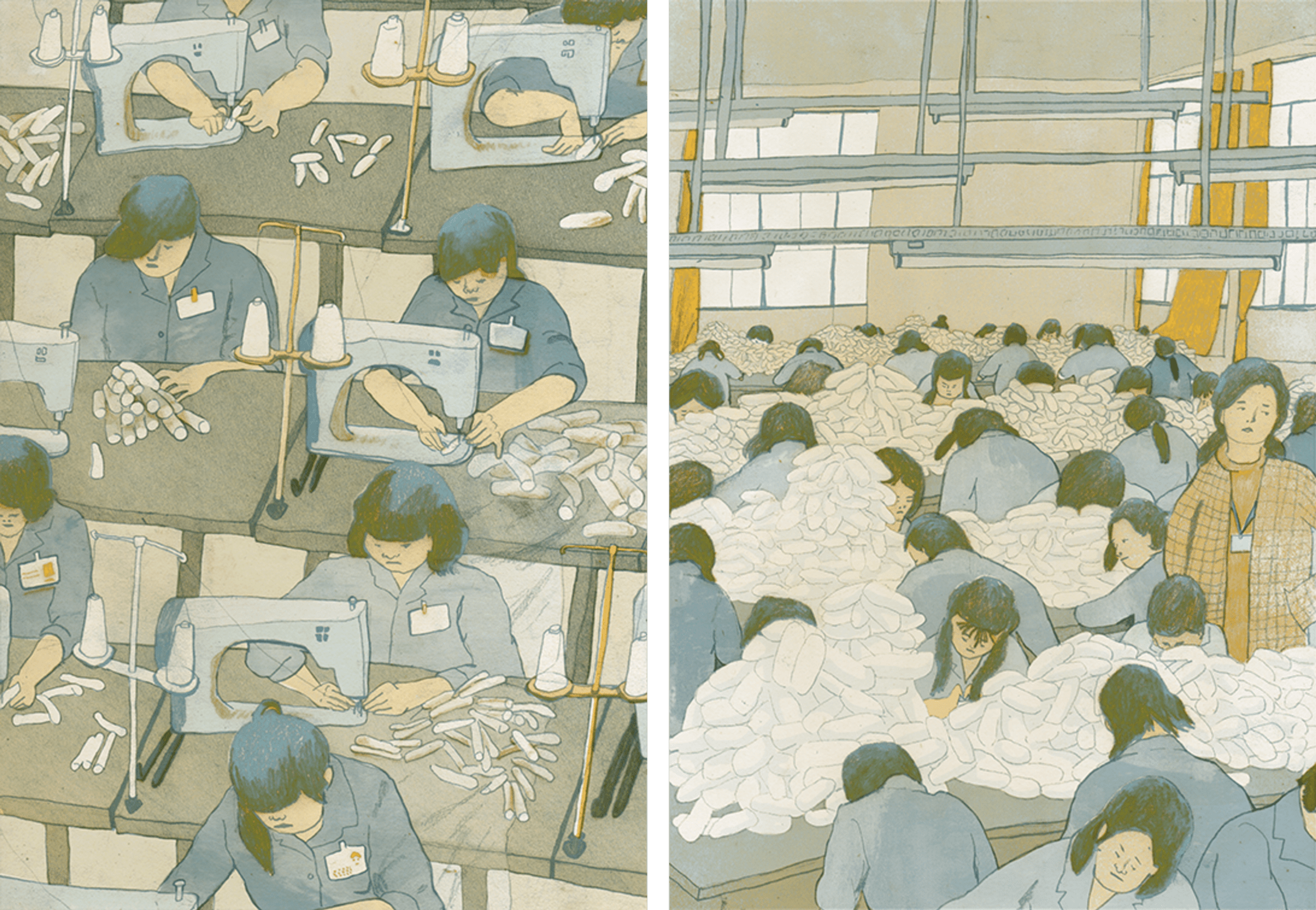

My recent project Pearl’s Daughters is based on the region where I was born and raised, the Pearl River Delta in China. Using archives, I followed the lives of migrant women who lived and worked in factories during the 1980s. They had left their hometowns and families for opportunities, yet most of the time they were seen as a collective workforce rather than individuals. These women were integral to change in a fast-developing region yet their voices have been overlooked.

Through research I found archive records as well as personal blogs and diaries, and I combined these different sources into one story. I created an illustrated book that acts as a literary collage or group portrait that responds to the shared experiences of this community of women. My intention isn’t to try to give an authoritative account of this time, but more to create an open conversation between past experiences, my work and the people looking at it.

What interested you about New River Head when you were starting your residency with Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration?

I was attracted to the complexity of the social history: I wanted to excavate stories from the past. For more than 300 years it was a busy industrial site supplying most of London’s drinking water. It was also a target during periods of rioting and war. But it has been silent for seven decades.

I was lucky to record its derelict state just before its restoration. I walked alone among its different buildings, looking for evidence of past activity and links to archived photographs and documents. Many of these documents tell conflicting stories, and I absorbed all of these when creating Lost Springs, Coming Spring, a large scale drawing that combines my direct observations and research.