A Q&A with Liz Williams, Archivist at Quentin Blake’s studio

by Liz Williams, Archivist at Quentin Blake’s studio

As Matilda The Musical is released on the big screen, we take a look at where it all began. Liz Williams tells us about her work looking after Quentin Blake’s archive of more than 40,000 drawings and how his illustrations for Matilda came to be.

How long have you been working with Quentin’s archive?

I've worked on Quentin’s archive since 2003, so will be celebrating my 20th anniversary next year!

What does an archivist do?

An archivist is responsible for looking after an archive, which is a collection of documents or other items created by a particular person or organisation. A key part of that is ensuring that we know what’s there – and where to find it! – so a lot of my time is spent cataloguing Quentin’s drawings.

How do you go about archiving Quentin’s work?

To catalogue any of Quentin's illustration work I start with the published book, checking through to make sure we have all the finished artwork, and seeing how any preparatory work might match up to that. Then I give each drawing a unique reference number, which is pencilled on the back.

This is used as a sort of 'shorthand' to refer to the artwork, so we can keep track of every piece. I fill in a record in our database for each artwork, describing the drawing (both what's shown in the picture and the condition of the physical sheet), its size, date and the materials Quentin used to create it. Digital images are then added to the record so we have a complete record of each drawing.

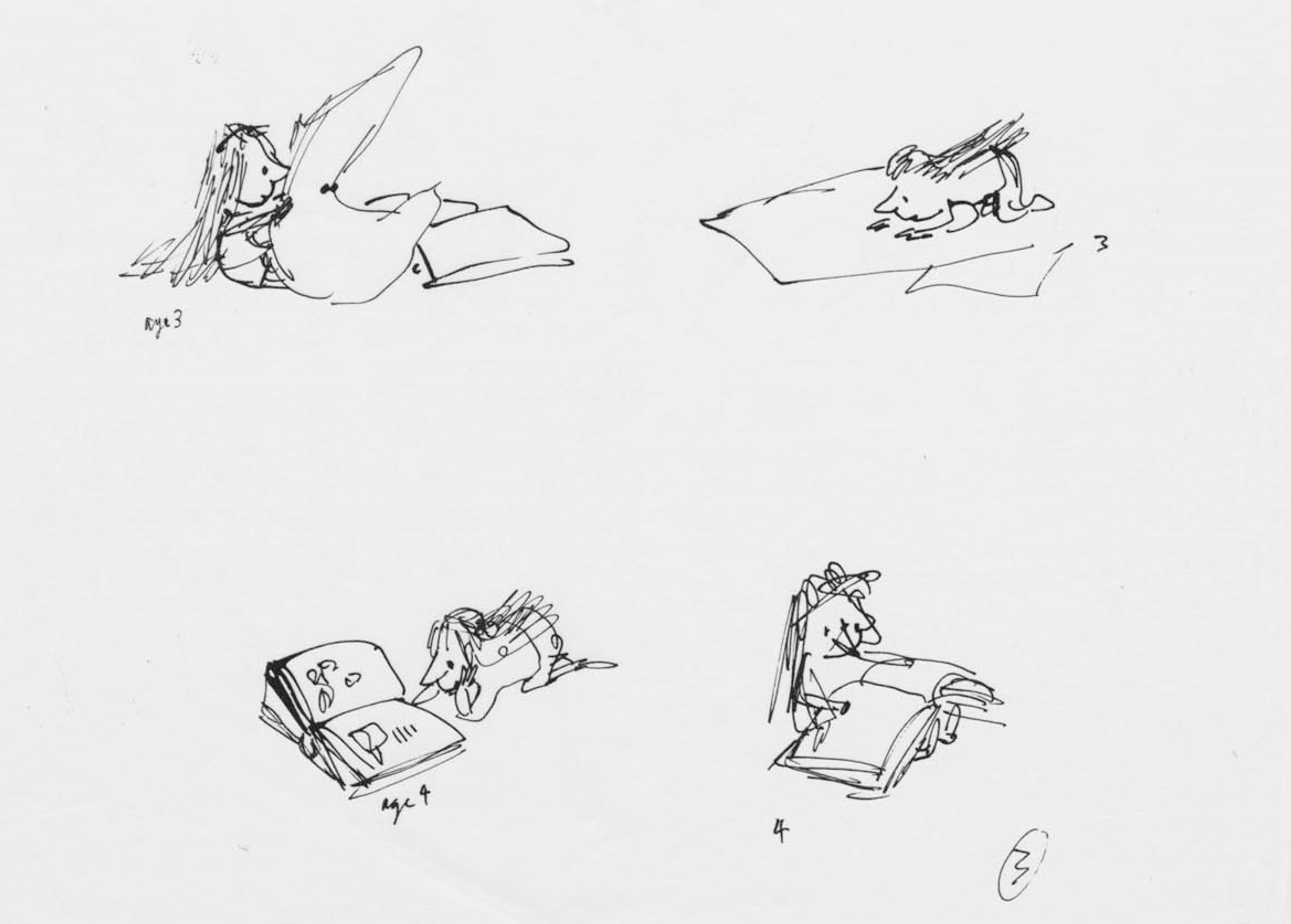

What are Quentin’s ‘roughs’ and ‘preliminary works’?

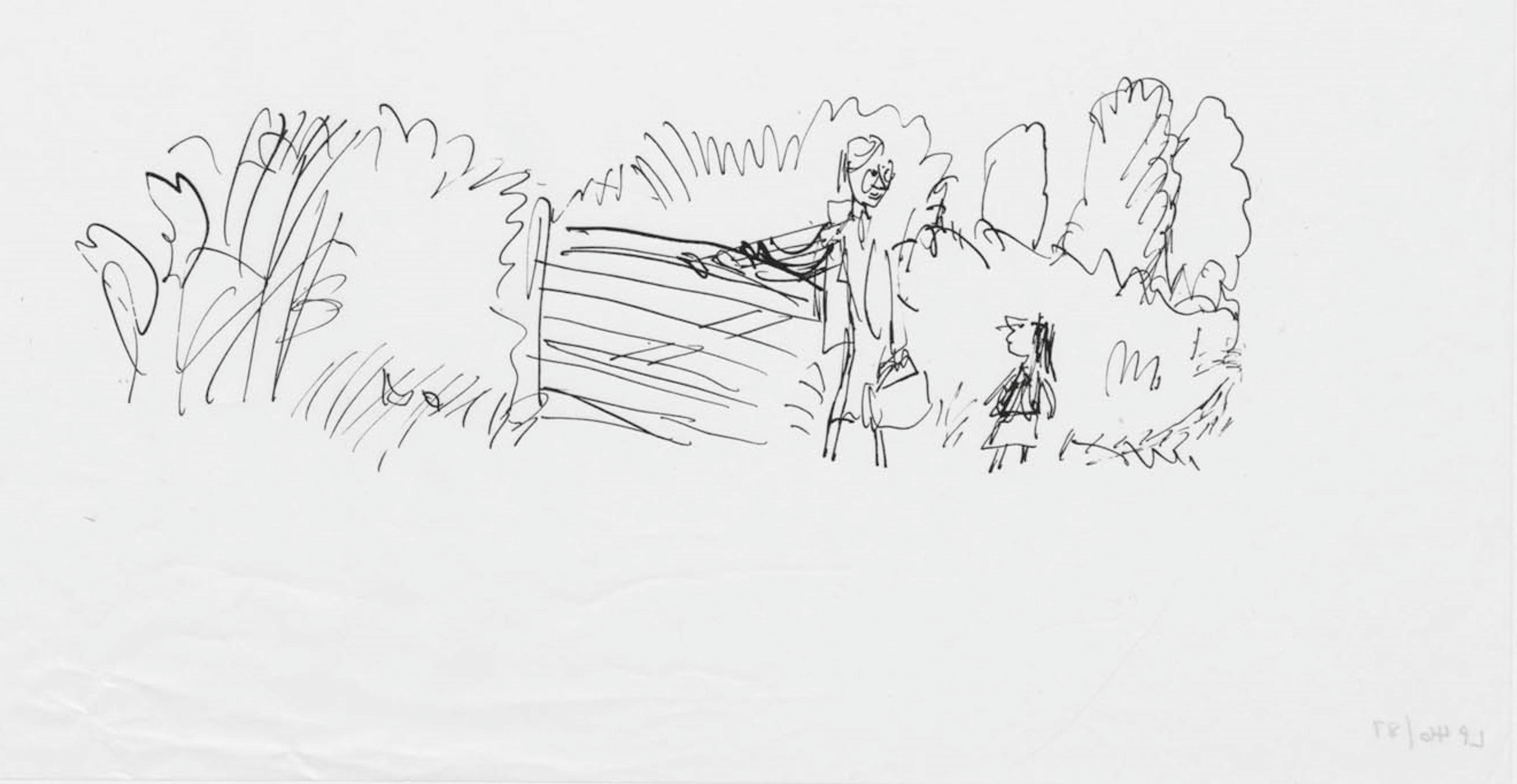

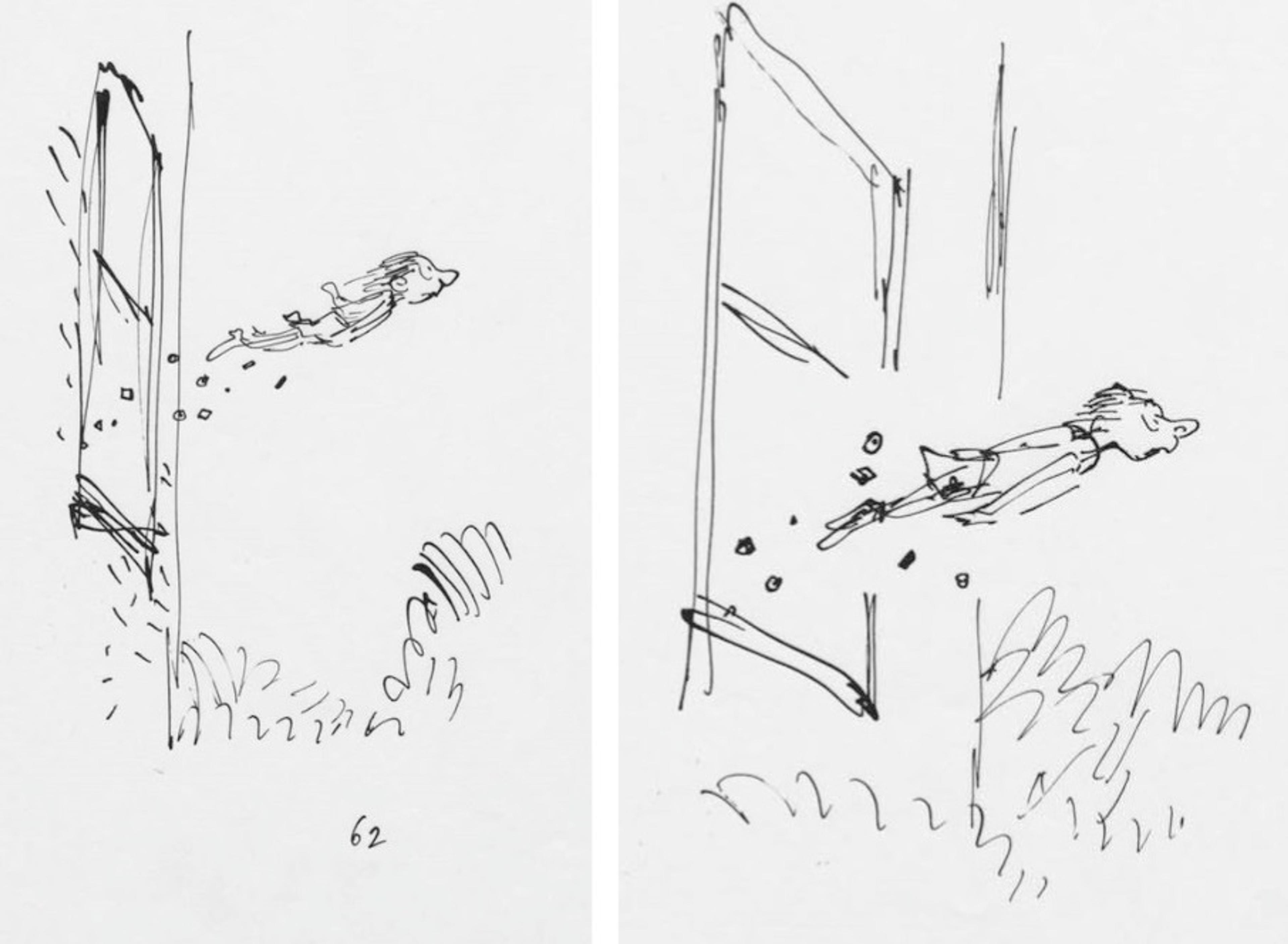

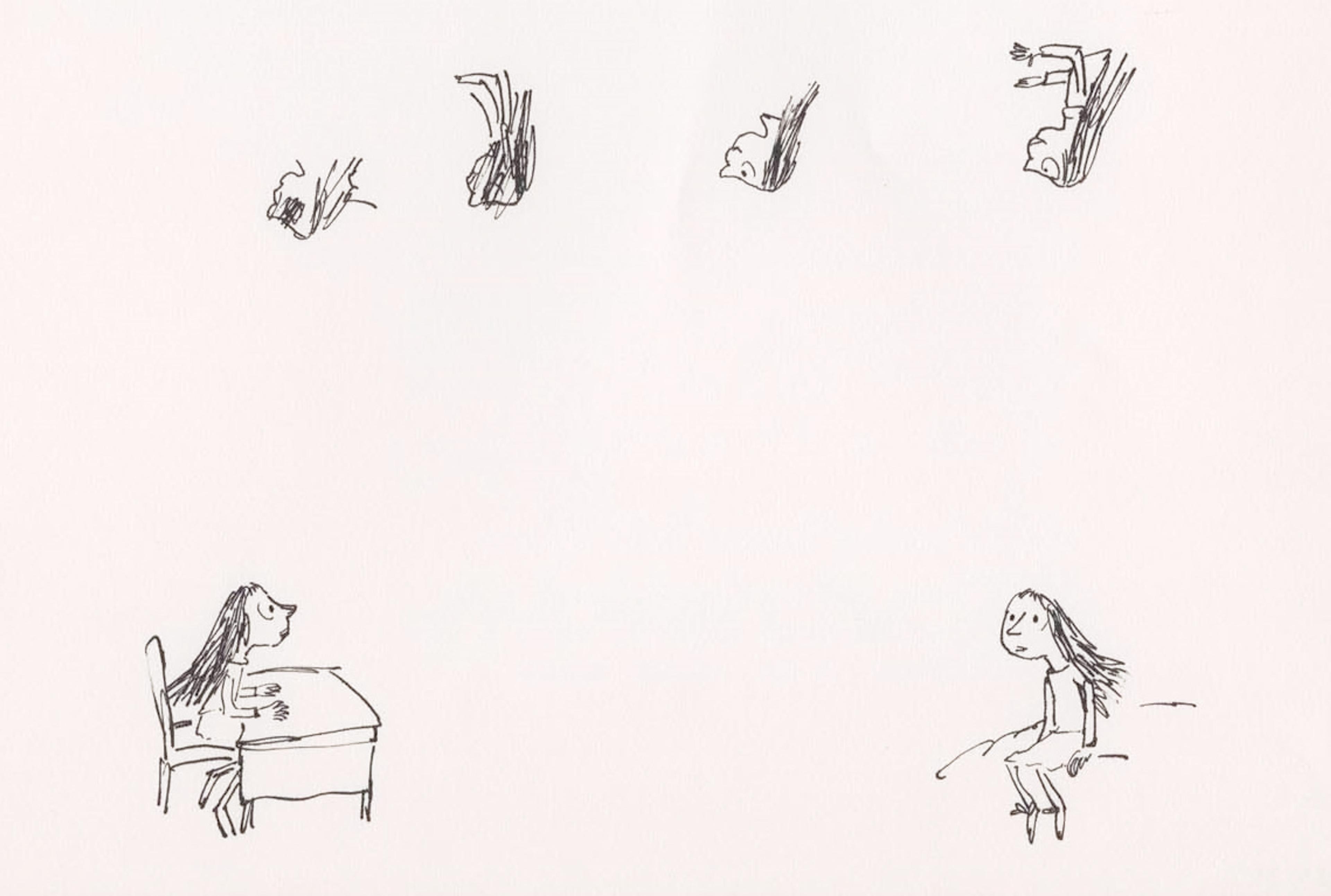

Quentin’s illustrations look spontaneous, but the number of drawings he does before a final illustration show that a lot of planning goes into them. ‘Rough’ drawings are usually Quentin’s first go at a composition, where he sets out where the characters are on the page and gets an idea of their gestures or expressions. Next, Quentin lays the rough drawing on his light box and puts a sheet of watercolour paper over the top.

At this stage, Quentin usually uses a dip pen and waterproof ink to create the outlines and details of the picture. He can have several goes at this, using a new sheet of paper each time; these are known as ‘preliminaries’ or ‘prelims’. There are sometimes several prelims for one illustration which never get to the stage of having watercolour added to them. In some cases, Quentin ends up with two almost identical drawings: he decides in the moment which one is ‘finished’ and which one is a ‘prelim’ (or, as Quentin often prefers to say, an ‘alternative’).

How did the Matilda prelims become final artworks?

Quentin hand-coloured his line drawings with grey watercolour, as the original Matilda was printed in black and white.

Over the years of their collaboration, Quentin developed a close working relationship with the author Roald Dahl. For Matilda Quentin sent copies of all the finished drawings to Dahl for him to see and comment on. In some cases Dahl’s comments resulted in Quentin doing a few new drawings, such as for the librarian, Mrs Phelps, who was originally shown as tall and angular.

How did Quentin interpret Matilda’s main characters?

As with any illustration commission, Quentin started with the author’s text, and worked to show in pictures what had been described in the words. Quentin’s early drawings of Miss Trunchbull were based on Roald Dahl’s original description, which made her look like some sort of military dictator. There are several prelims showing Quentin’s experiments with hairstyles and clothing, before Roald Dahl changed his text to describe the fearsome Headmistress who has become notorious…

In the text there is a lot less descriptive information about Matilda herself, but Quentin felt it was important that she should be a tiny figure pitted against grown-ups. The prelims include a lovely page of ‘workings out’ where he has several goes at drawing her face: trying to capture the essence of her being very young but also very wise. The result is a little girl with a face much older than her years